Frequently Asked Questions

While the level of understanding of voice acoustics that a voice teacher needs to have is neither exceedingly high nor difficult, it usually takes time and several passes for novices to acoustic science to catch on to the ideas. I therefore often encounter persons for whom information that I thought had been clearly presented is still not clear. I will use this FAQ site to try to make that information understandable. I encourage readers of PVA to let me know of lingering questions they have and I will include here the more frequently asked questions and their answers.

1. I still don’t understand what a formant is? Is it a place in my vocal tract?

A formant is an acoustic characteristic of the vocal tract tubing, specifically a natural resonance of the vocal tract. It is a frequency area (you can think pitch area if you like) at which the vocal tract is very responsive to sound vibrations. Any harmonics introduced by the vocal folds into the vocal tract that are in tune with or near a formant peak will excite stronger vibrations within the vocal tract and will be radiated from the mouth with more strength. Harmonics that are not near a formant peak in pitch will tend to be weakened. We are able to tune our formants—especially the first two formants—by changing the shape of our vocal tracts. We do this simply by pronouncing different vowels, since vowels are defined or identified by the locations of the first two formants.

A formant is not a particular place within your vocal tract, rather it is a characteristic of the entire vocal tract, though parts of the vocal tract have a greater influence on some formants than on others. The first or lowest formant is very much influenced by the pharyngeal (throat) part of the vocal tract, while the oral cavity has a greater influence on the second formant. Formants one and two are also perceived or felt somewhat more in the pharynx and mouth respectively.

2. Is the first formant like my chest voice and the second formant like my head voice?

The first and second formants are present in all laryngeal registers, so a lower formant is not just for lower registers nor a higher formant for higher registers. Formants do however play important roles in acoustic registration. Acoustic registration has to do with timbral qualities and effects that we may hear as vocal registers, but which are caused by harmonic interactions with formants, and can be independent of laryngeal adjustments.

The first formant’s relationship to the harmonics of a sung tone plays a strong role in our perception of register. When there are two or more harmonics below the first formant—that is, when singing pitches more than an octave below the first formant of a vowel—the voice is in open timbre and sounds chesty in register. When singing within an octave below the first formant (with only one harmonic below F1), the sound is in close timbre, turned over, and sounds more mixed in register. When the pitch you are singing matches the first formant, the voice will sound very heady, regardless of the laryngeal register. That acoustic situation (H1 = F1) is called whoop timbre.

3. Why doesn’t a voice always “turn over” on the same pitch?

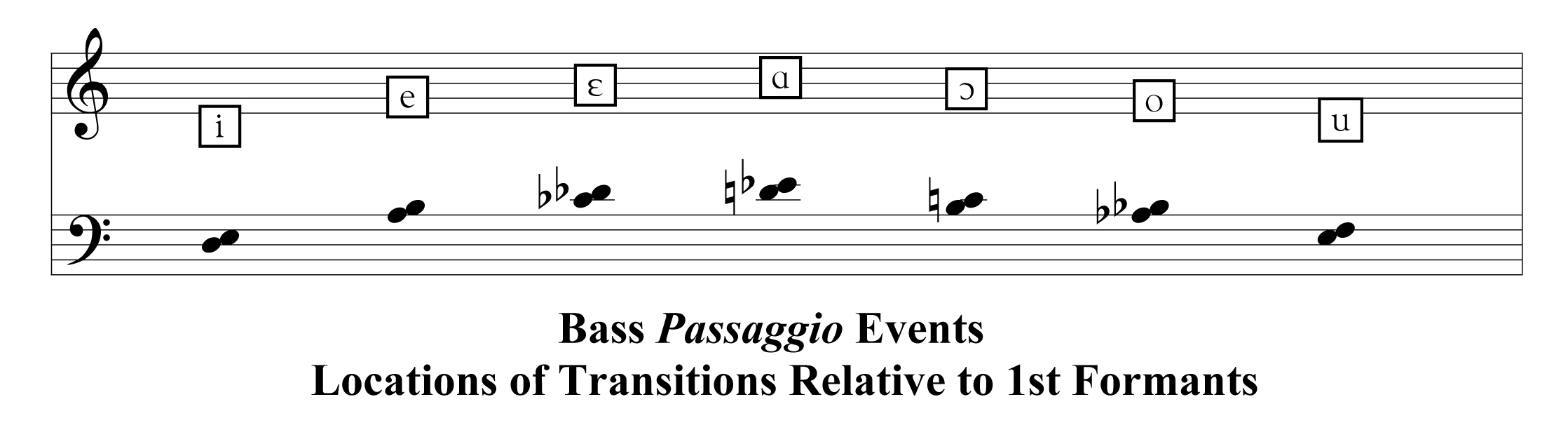

If “turning over” were primarily a laryngeal event, we would expect the voice to turn over, or shift registers at the same place regardless of the vowel. However, a voice turns over when the second harmonic of the pitch one is singing rises above the first formant of the vowel one is singing. Vowel formants vary in location by as much as an octave—an /i/ first formant is an octave lower than an /a/ first formant, for example. So the voice turns over and the timbre closes in a parallel relationship with vowels’ first formant locations. This is shown in this chart:

Formant locations are shown with IPA symbols in boxes on the treble clef, and each vowel's note of turning is notated on the bass clef. Pitches sung below the notes of turning are in open timbre for the particular vowel. Notes between the pitches of turning and the formant boxes have turned over and are in close timbre. Notes sung at the pitch of the formant boxes are in whoop timbre for that vowel.

4. This acoustic information seems too complicated. Why do I need to know it? Does it really make that much difference?

Any truly new, unknown area seems daunting at first, like learning a new language or musical instrument. But once you get past the initial challenge, it becomes easier, until you get to the point at which you wonder why it ever seemed difficult. I am personally convinced that understanding voice acoustics and how to use it in the studio will make any voice teacher much more efficient, and can form the basis for much creative, productive, specific problem solving. While acoustic pedagogy is only one part of what we do, it addresses a part of singing that is very receptive to change and can make a remarkable difference. Finding better acoustic shapes for the vocal tract creates beneficial feedback on the larynx, making the vibrator more efficient, generating more power for less pressure, and even improving breath efficiency. It also explains many of the vocal challenges students face, and clarifies their solutions.

5. Does acoustic pedagogy make lessons too technical and technological and stifle artistic expression?

The main goal of voice instruction is to enable beautiful, creative expression through singing. Any technical approach can become too intrusive, result in overly complicated micromanagement, and inhibit free expression. Technique needs to be the servant of vocal freedom and efficiency, so that artistry is freed from constraints and limitations. Since skillful acoustic singing maximizes freedom, power, dynamic flexibility, and beauty, it serves the goals stated above very well. Range development and register transitions can be much more reliable and quickly mastered. Furthermore, while some technology can be useful along the way, once the principles and predictable locations of acoustic events are understood, acoustic pedagogy can be done without any technology in the studio.